The idea that you must prove you are an individual human before entering an online store is a ludicrous relic of the past. Bots have become synonymous with evil when they should be seen as enablers that aren’t going away – for better or worse. Time for them to work for us, not against us.

On the one hand, consider a recent article in the Wall Street Journal:

Nike to Crack Down on Sneaker-Buying Bots, Dealing a Blow to Resale Market

On the other hand, every week, a new consumer business data breach brings about new knee-jerk reactions and pushes us further into a more frustrating online customer experience.

These are two symptoms of an increasingly broken digital engagement model for consumers.

B2B vs B2C

Business-to-business digital engagement practices evolved from a long history of distant geographic relationships. Delegations, contracts and financial intermediaries grew to scale business to incredible volumes and geographic breadth. This scale would never have been possible if the CEO had to personally sign into every supplier website, place every order and make every payment from their personal wallet.

During this time, business-to-consumer digital engagement practices have not evolved at all. An online store still assumes that a person ‘walks’ into that store as they’ve done for thousands of years. If the consumer isn’t using cash (difficult in an online store), they have to provide some ID – not to prove who they are – but to prove that they have access to the non-cash finance in their name – i.e. know your customer has the money.

Early in my lifetime, you needed to show a driver’s licence to pay with a cheque to see if the names were the same. Now you have to use an email/password/MFA combination to authenticate via a payment provider’s interface and return a token to the merchant to prove you have access to the non-cash finance.

Somewhere along the way, the need to prove that the non-cash finance is available became a ‘need’ to capture as much data as possible. This ‘allowed’ the business to ‘serve you better’ and market to you independent of any financial requirement – sometimes that includes the store keeping your driver’s license details too.

The idea that you must prove you are an individual human before entering an online store is a ludicrous relic of the past.

Untapped Digital Consumer Opportunities

Digitisation should offer amazing opportunities for consumers to discover and acquire amazing products from anywhere in the world, whenever they want them.

The global digital marketplace is too large for any individual consumer ever to know and offers an extraordinary opportunity for intelligent search, ‘AI’ machine learning services etc. Your current Google search result is more like an old local phone book when compared to the vast size of today’s global digital marketplace.

While Amazon markets itself as the ‘everything store’ – it only covers the merest fraction of the online consumer market. Even then, I defy anyone to stroll through the Amazon aisles confident that they found the best supplier, product and price to meet their requirements in the marketplace.

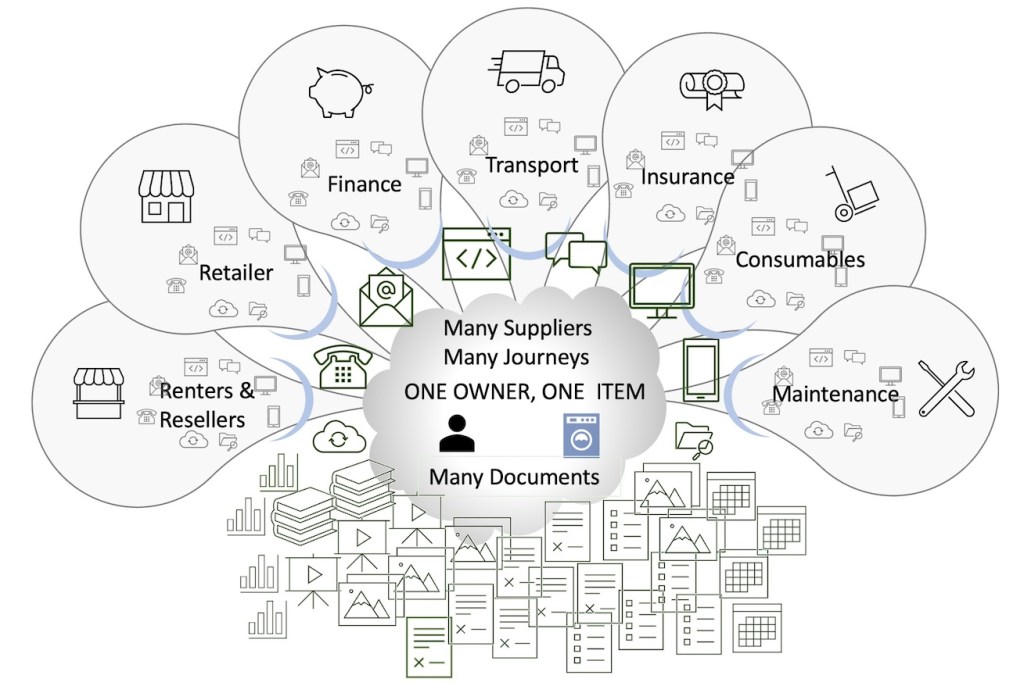

To tap into the potential value of global digital commerce, consumers must delegate their shopping to ‘digital buyers’ – authorised agents that are always scanning the market for buried treasure and buying it ‘on the spot’.

Unfortunately, today, consumer-facing search APIs are restricted to discourage high-volume scanning. eCommerce website and app interfaces do their best to get you to prove that you are indeed the unique individual who has entered the store.

There’s an ongoing battle between the eCommerce developers, search platforms and the ‘bot’ developers to be able to discover and interact with services programmatically. To a large extent, this battle is being fought by businesses that still try to be your only store in the area (or at least in your attention span).

Bots have become synonymous with evil when they should be seen as enablers that aren’t going away – for better or worse.

I’m confident that this engagement model will evolve, but I hope it won’t take thousands of years.

What to do?

Developers should redirect some of the time fighting the bots to making it easier for customers to delegate to their authorised buying bot – leading to more sales for the retailer and better consumer experiences for the customer.

In the short term, you can help by lobbying your service providers to offer an option for you to formally delegate some of your account access to approved and secure programmatic buying services.

You must be logged in to post a comment.